At noon every weekday St. Viateur St. is full of Ubisoftoids, packs of young game designers who pour out of the old Peck Building hungry for lunch, their appetites sustaining a dozen new local restaurants. Weekend mornings, the cafés are jammed with snaking lineups and fancy strollers, trikes and bikes parked three deep on the sidewalk.

Just when I thought Mile End couldn’t get any trendier, a recent study by Concordia and University of Toronto researchers set out to study its trendiness. For over a decade, such studies and cool-hunting articles have had the effect of changing the neighbourhood they’re observing. The result: life in Mile End gets more chic.

I may have been part of the hype.

For three years, I wrote this blog. I started when our daughter Amelia was tiny and I spent all my time pushing her around the block in the stroller. Strolling with my baby made me look at every fruit tree and old person in my neighbourhood with a new sense of wonder. I wanted to champion the details that fell through the cracks in media coverage of the area.

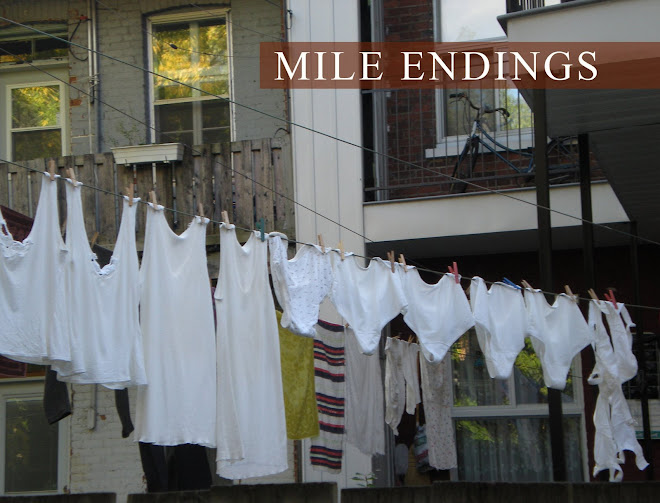

I’d lived here for 20 years and was obsessed with keeping track of what was lost every time a musty local business metamorphosed into something shinier. I wrote about Barry Shinder’s 80-year-old cap factory, Norman Epelbaum’s time capsule-like photo studio on Park Avenue, and the mysterious corsetières at Lingerie Rose Marie across the street. I was Mile End’s E.B. White, or at least the self-appointed hyper-local bard of the disappearing family business.

Yet every ending also promises a new beginning. I wrote about those, too. Who could object to gardening in the hard-packed earth around tree squares? Or urban beekeeping? Old people may be disappearing from the area but there are more strollers than ever and the next generation of neighbours is set to stay here for a while. The community-building group Ruepublique is full of committed people in their 20s. They seem to love the neighbourhood as much as I do and are working to improve the area’s public street space.

Then, I’m not sure when, or exactly why, but a sense of neighbourhood fatigue set in.

I still walk around, but Amelia is almost four now. She pedals her own bike, and has her own opinions about what we do: (“Mom, this is not interesting to me.”)

I look at the aqua storefront of the brightly-lit new David’s Tea chain on St. Viateur, or the shops on Bernard selling herbs and sea salt, or vintage glasses frames, and I think: “My work here is done. Everything has changed, there is nothing ungentrified left to keep track of.” (“Mom, this is not interesting to me.”)

But of course, cities and neighbourhoods are always changing. There is always something to notice.

My chronicle of mileendings may have run its course for now, but Amelia is alert to anything new that pops up on her radar, every string of Christmas lights, or the (fortunately brief) re-appearance of the gigantic Nokia-Virgin Mobile reindeer on St. Viateur.

I imagine someday in the faraway future, a thousand trends and changes from now, she’ll look back and remember how it used to be when she was a kid, the Mile End of the 2010s, back in the day.

P.S. To all readers of this blog: thank you.