On a warm evening when I open the back door and the whole alley seems to be in bloom I hear him. A crazy burst of tuneful whistling. A loud whit-whoo! as if in appreciation of a real looker.

It's my favourite and most mysterious neighbour across the alley: the parrot.

This time of year his calls loop out of his third floor window and into our lives.

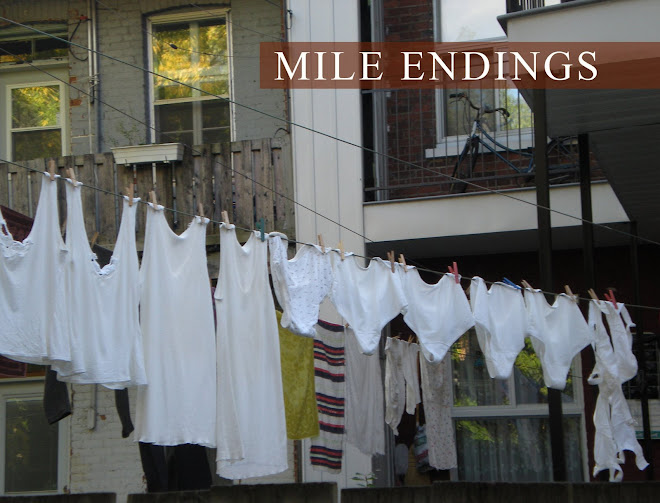

He has captured the beep beep beep of a truck backing up, and the screee of a squeaky clothesline. In the beginning, I didn't know these noises were coming from a parrot. But there's a reedy resonance to the toots and squeaks. Plus, he remixes the alley sounds with trilling whistles and sends them spinning back out again.

His loopy sounds are part of my summer. Yet inside his third-floor window, the parrot has always been invisible to me.

There's something strange about introducing yourself to people you've lived next to for a decade and a half. 'Hi, I've been meaning to say hello for a while now...' ?

The thing is, since I've become a mother, I talk to neighbours in a way I never used to. It feels natural, maybe even important. Our daughter opens gates, toddles up front walks and expects to go inside the neighbours' homes. Everyone is someone to wave at and every doorway is there to be explored. Like the parrot, she has no sense of boundaries.

She's my incentive and my role-model as I walk out my door and around the block to the front of the parrot triplex. Some kids are playing on the stone patio with a toy glider.

One boy's mother, a pretty, shiny-haired woman named Bia, turns out to be the parrot's owner. I tell her I've been hearing her bird for years. She thinks I'm there to complain. "It bothers you?"

"That's how I know it's summer!" I say. "I love it."

Bia tells me the parrot is an African Grey named Max.

Max was a gift to Bia from her husband Mario, 17 years ago, not long after she moved to Montreal from Porto, Portugal. Now they have two sons, but back then Bia was home alone while Mario went to work. She didn't speak much English or French and felt isolated.

"My husband works a lot," she says. "Probably why he got me the bird," she adds with a wry smile.

"Max is company. When you have no one to talk to, you talk to the bird. In the morning you say good morning, the bird says good morning back."

It has taken me 15 years to get this far, so now that I'm finally on Bia's patio, I go all the way. I ask if I can meet Max. Bia shows me upstairs, past shelves of bird figurines, through a spotless apartment where her teenaged son is listening to music in his room.

"I always thought Max was a male --until last year when she laid four eggs!" Bia tells me, adding that if she'd known, she might have mated her. African Greys are highly sought after and she says she could have sold the chicks for $1500 each.

She opens the door to the utility room at the back of the apartment where there's a washing machine, a step ladder, a window out onto our shared alley, and a spacious bird cage.

Max surprises me by being smaller than I imagined. Her soft, grey, white-rimmed feathers look like petals and she has a brilliant red tail.

I stare, not sure what to do now that I'm face to face with the invisible --almost mythical--alley creature.

I stare, not sure what to do now that I'm face to face with the invisible --almost mythical--alley creature.The bird ruffles her feathers, wary of me. "She's afraid," Bia explains. "That's what she does when she sees someone she doesn't know."

Max doesn't realize I'm a devoted listener. She cocks her head to examine me with one yellow eye and then the other.

Then she gives a quiet squawk, "Hola."

Another surprise. I didn't know my-neighbour-the-parrot could talk. Apparently, when you're within talking distance, she does.

"Hola! Hola! Hola!" I reply, I'm a giddy fan with a backstage pass.

"She speaks Portuguese, like me," Bia explains. "She imitates Mario's whistle, the phone, everything."

While we're in her room, Max is not loud at all. No beeping or hooting or screeching. She looks at us, makes a little Portuguese conversation, and listens.

"She makes a lot of dust," Bia is telling me. "Dander. Every three days I have to clean the cage. And she has to have showers. And her wing feathers trimmed. You get tired," she confesses, about the parrot care. "And they can live for 95 years!"

Max shifts and twists on her perch, eyeing us with curiosity.

When Max is an old parrot, my daughter will be an old lady. They have so much in common. Just this morning, when I was changing her diaper, she heard the sound of a truck backing up, and hooted along à la Max. "eep, eep, eep, eep!"

When Max is an old parrot, my daughter will be an old lady. They have so much in common. Just this morning, when I was changing her diaper, she heard the sound of a truck backing up, and hooted along à la Max. "eep, eep, eep, eep!"Improbably, I imagine them as neighbours in the far-off future. Max will have new sounds in her repertoire by then, but every once in a while she'll call out a piercing beep beep beep, and this will remind her neighbour, a baby-faced old lady, of the olden days, of growing up along the alley, back at the beginning of the century.